Spurensuche in Bournemouth, Großbritannien

von Silja Wiedeking, 2004

Bournemouth’s D-Day

60 years ago

60 years ago, on 6 June 1944, the Allied troops landed in Normandy. The D-Day landings were the beginning of the end of the German Nazi regime. By 1945 the greatest war in human history was over.

“Bournemouth was a front-line town then,” Eileen Barker recalls. “Many people don’t know that nowadays.” - Not many remember the past of Bournemouth.

Bournemouth since the outbreak of the war was a ‘sorting point’ for international troops, evacuees, and Dunkirk survivors.

Mrs Barker remembers this time well. “I was only a girl but when they brought the men from Dunkirk, us children were asked to go to all houses and ask for soap and all we could get for the thousands of men, so that they could at least clean themselves up.”

Her husband John Barker was an evacuee himself. As a boy he left London in 1940 with his family. “We were bombed out three times at home so we left.” The family moved to Boscombe but not many people lived there anymore. They had left out of fear: “We lived close to Wilfred Road, where three bombs had detonated in a row.”

Mrs and Mr Barker are both in their mid-70s now. They were only teenagers at the time of the Second World War.

To them it was an exciting time. Mrs Barker especially remembers dancing with American soldiers at the Red Cross dances. “I think our parents were very concerned about the war but we did not realize that.”

But the war was real and the Barkers think it is sad that very few people remember the war and that less and less people know about the past of Bournemouth.

The people in the town

In 1939 Bournemouth became part of the front line in the war against Germany. Together with Poole it was the third largest embarkation point for overseas troops in Great Britain. Soldiers from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and later the United States were stationed in the town.

About 144,450 people lived in the seaside resort at the time. Many of them, like Mrs Barker’s parents, worked for the home guard. “My father was too old for the war so he became an air raid warden. At night, during raids, he spent a lot of time calming down old ladies.”

From the beginning of the war hundreds of children from Southampton and Portsmouth were evacuated to Bournemouth. The town was deemed to be safer than the two naval cities. Historian John Walker, who is now 70, was a little boy when his school class was sent away from Portsmouth in late 1939: “I was with my friends, but we certainly knew that danger was around us.”

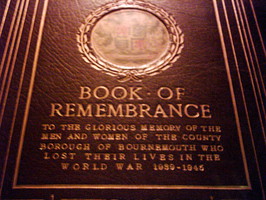

Bournemouth lost 575 servicemen and civilians during the war. Their names are listed in the Book of Remembrance in the Town Hall. The list is long and as a Town Hall official says, names of dead soldiers are still being added today.

The number of international servicemen killed in Bournemouth has not been confirmed.

Overall there are 24 memorial stones for the people killed in the war. Most of them are to be found in St Peter’s church in the town centre.

The piers, the beaches and the town

After the disastrous defeat of the Allied troops in Dunkirk and the thousands of survivors coming to the town, the fear of a German invasion rose.

On 3 July 1940 the Bournemouth and Boscombe piers were partially blown up to prevent German boats from landing.

Mrs Barker remembers: “after Dunkirk my mother used to keep a racket at the door because she thought the Germans would come straight over.”

The seafront was closed to all but the military. Scaffolding in the water was meant to prevent enemy troops from landing, and barbed wire covered the sand. It was rumoured that the beaches were covered in mines. On the cliff tops army vehicles and anti-aircraft guns were stationed.

Most schools were closed and turned into hospitals and shelters for evacuees. “That is why I had only little education, the schools were needed for the war,” Mrs Barker thinks.

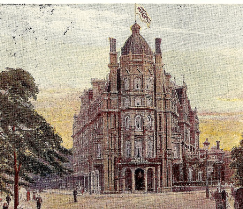

All but four hotels were requisitioned by the military or the British authorities. The Town Hall became the administrative centre.

The air raids

A Bournemouth Times article from 8 December 1944 stated that since 1940 there had been 50 air raids on the town. 2271 bombs had been dropped, 13,590 buildings damaged or destroyed, 219 people killed, 507 injured, and 401 made homeless.

Bournemouth, the town that had been found safe in the early days of the war, was the target of German bombs.

Mrs Barker still owns her mother’s diary in which she counted every air alert – she stopped after 708.

Bournemouth was hit by one major attack on 23 May 1943.

Mr Barker was just about to say goodbye to a friend who visited him that day: “At about 1pm my friend left and three German planes came flying over our house at only 150 feet! We rushed into the house and hid under the stairs, it was frightening.”

The Lunchtime bombing was the most devastating attack on the town.

Beales, then the most famous department store in the south, burned down completely.

The Metropole Hotel at the Lansdowne, where KFC is today, took a direct hit. Most of the Canadian soldiers who stayed there died: “A friend of mine was a bus conductor,” Mrs Barker says, “the day after the raid she drove past the Metropole and the bodies of dead soldiers were still hanging out of the windows.”

The town was in shock, “at this time we could even see the burning fires of Southampton, the skies were red”, she says.

The troops from overseas: Francis Max McKenzie

The town was crowded with servicemen. Most troops stayed in Bournemouth only for a few weeks’ training or to wait at one of the many army reception centres after landing in Poole.

Francis Max McKenzie was one of them. He was a young soldier from New Zealand born in 1916 in the city of Dannevirke. After school he became a partner in his father’s printing business.

But when Great Britain and New Zealand declared war on Hitler on 4 September 1939 military service became compulsory.

On 14 August 1941 he left for England by boat. He arrived in Bournemouth in October and stayed for only three weeks.

On 23 June 1943, just one month after the lunchtime bombing on Bournemouth, Pilot Officer McKenzie’s Stirling bomber was shot down after an air raid on the German town Mülheim. He told his crew to abandon the plane, all six baled, five survived.

Francis Max McKenzie died when his plane hit the ground. But he saved his crew.

The end: D-Day

“On the night before D-Day all the roads were full of tanks and the bay was filled with boats as far as you could see, all preparing to leave for Normandy.” Mr Barker says. “The next day all but one were gone. I went to school and all day long RAF squadrons would fly over to France.”

Bournemouth had prepared for D-Day, or Operation Overlord, and after 5 June 1944 the town was deserted. Most soldiers had been sent on the boats to Normandy.

“Twenty of the men I knew never returned from Normandy, they died. And the soldier I used to dance with lost one leg.”

Mrs Barker says the troops did not return to Bournemouth after D-Day. The war for the city was over.

The invasion of Normandy marked the imminent end of the war, and Bournemouth had contributed to it.

The past of Bournemouth is unknown to many people. Therefore it needs to be told, reported on, and written down, as long as eyewitnesses like John and Eileen Barker can tell us about it.

D.J. Bowden was wireless operator and air gunner in a Stirling I, 149 Squadron No W7628 OJ-B

On 23 October 1942 his plane started from Lakenheath to Genoa during the bombing of North Italy

His plane ran out of fuel while returning to base. At 00:03 am the plane crashed 5 miles north of Rochester, all seven crew died

D.J. Bowden died aged 22

C.J. Bond was an air gunner in a Stirling I, 149 Squadron No R 9329 OJ-V

On 20 August 1942 at 20:45 his plane started from Lakenheath, in Operation Gardening, dropping mines at the French Coast.

His plane crashed 19 miles southwest of Torbay, Devon, all seven crew died

C.J. Bond died aged 19

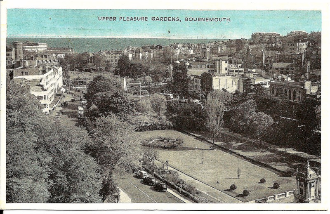

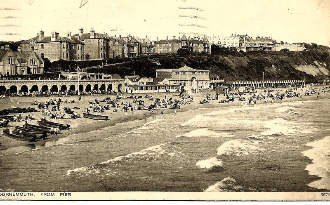

The Seaside Resort before the devastating air raid during the Second World War

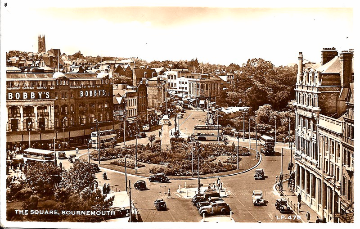

Bournemouth after the Second World War

© Silja Wiedeking